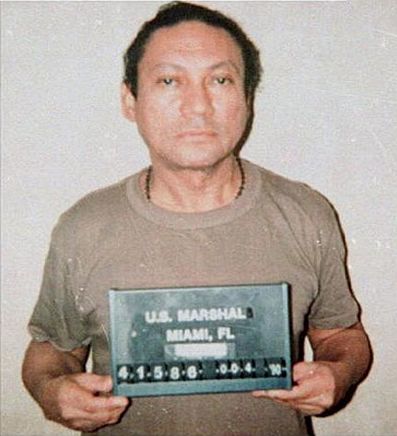

Reagan and Noriega

An Adapted Section of My Thesis

After 1985, Manuel Noriega was transformed from a leader into an issue. The Reagan administration had substantial knowledge of what Noriega was up to in the early 1980s, however political conditions in the United States were not conducive to an aggressive agenda in Panama. That began to change however, when the first bombshell report to be released to the press indicted Noriega as being responsible for Spadafora’s death, as well as maintaining “tight control of drug and money laundering activities…”[1] As more and more media attention began to be directed towards the illegal drug trafficking of Noriega, the repression of Panamanians, and the PDF’s corruption, conditions began to become conducive for political gain in opposing Noriega.

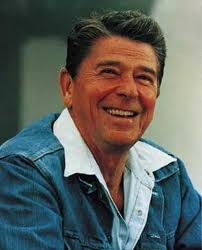

While Noriega still had allies in the American intelligence and defense networks who thought him to be more of an asset than a liability, American domestic politics were changing, forcing a rethinking of foreign policy. 1980s Americans saw the rise of drugs, such as crack and cocaine, as being one of the most prominent threats to the morality of society. Correspondingly, conservative politicians sought to use and drive this fear as a wedge issue, which could potentially draw moderate or single issue voters to the Republican Party. Single issue voters were especially sought, since crime control is one of the few issues which appeals to broad segments of the electorate in a political climate which since the 1960s has seen the deterioration of support for broad based parties.[2] While crime control has always been a core function of the government, as late as the 1950s, it was not a partisan issue. Barry Goldwater was among the first politicians to use crime control as a major rallying cry in his failed 1964 presidential run, with Nixon being the first President to successfully capitalize on the issue.[3]

The wars on crime and drugs really picked up steam with Reagan’s White House. In October 1982 Reagan officially announced his war on drugs with Vice-President Bush at the head of the campaign.[4]

The result was the increase of the FBI’s drug budget from $8 million in 1980, to $95 million in 1984. The Department of Defense’s drug budget more than doubled in this same time period despite the fact that nearly every other federal program was undergoing budget cuts, including rehabilitation programs for drug addicts.[5] By depicting drug and crime control as being an issue of good versus evil, Reagan and other conservatives, successfully severed working class white Americans from their traditional place in the base of the Democratic Party. Race cannot be ignored in this transition as Reagan made sure to highlight the connection between hard-drug use and the status of minorities in the violent inner-cities. In so doing he expanded the post-Watergate base of the Republican Party, successfully drawing attention away from his own social policies which were destroying communities. Reagan emphasized the values of personal responsibility coupled with harsh punishments for offenders.[6] Sociologists have since described crack as a “godsend to the right” writing,

“They [the right] used it and the drug issue as an ideological fig leaf to place over the unsightly urban ills that had increased markedly under Reagan administration social and economic policies… For the Reagan administration… America’s drug problems functioned as opportunities for the imposition of an old moral agenda…”[7]

From 1985 through 1987, with drug issues ever more important, the Reagan administration shifted its stance moving progressively further away from support or even toleration of Noriega. In March 1986 Senator Jesse Helms (R-North Carolina) launched an investigation into Noriega citing his desire to “turn the canal over to a viable, stable democracy, not a bunch of corrupt drug dealers.”[8] Shortly thereafter, Senator John Kerry (D-Massachusetts) used his Foreign Relations Subcommittee on Terrorism, Narcotics, and International Communication to become a forum for attacking Noriega. These hearings produced public condemnation of Noriega’s dealings with Cuba and the contras, while putting Panama on the map as the money-laundering capital of the region.[9] Perhaps most important, 1986 was the first year in which the major narcotics crimes of the Noriega government began to come out to the public. Congressional investigations that year, showed that in 1984 right around the time that Panama was getting credit for holding elections, Noriega was also sheltering hundreds of members of the Medellin cartel including the notorious Pablo Escobar.[10]

Later that year Noriega lost two important allies in the American bureaucracy in CIA Director Casey and National Security Council staffer North. While these were two of the more important individuals, the bureaucracy as a whole was shifting more and more in favor of the Department of State who opposed Noriega. From 1986 on, Washington was looking to remove Noriega and attempted to do so covertly at least five times before the 1989 invasion.[11]

In 1987 another bombshell report was released by Noriega’s Chief of Staff Roberto Herrera. Herrera was supposed to become the new head of the PDF as per the 1982 power-sharing agreement, however once in power Noriega had no intentions of leaving. In early 1987 Herrera was phased out of the PDF and Noriega soon organized his retirement. In response, Herrera went to the media, perhaps to attack Noriega, but probably more for his own protection. For days, Herrera conversed with the media about Noriega’s illicit murders and acts of corruption, even admitting his own role in rigging the 1984 elections. Though Herrera was one of the very instruments by which Noriega committed his crimes, by the third day of media attention Herrera was an unlikely symbol of the opposition.[12]

The repercussions of this were enormous for Panamanian and American politics. In Panama, Herrera’s actions created a split within the PDF, continuing the erosion that began a few years before. The accusations against Noriega also spurred violent demonstrations and attempts at reform, though Noriega would successfully outmaneuver and out power his rivals. Still, the vast majority of Panamanians now supported Noriega’s removal. In fact, one Gallup poll taken in August 1987 showed that 75% of the populations of Panama City and Colón favored Noriega’s resignation.[13]

In America, the Reagan administration was divided about how to respond, yet Congress was tough with its words. In June 1987 the Senate voted overwhelmingly to pass a resolution seeking Noriega and several other high ranking PDF members’ resignation. Despite the coalition of liberal and conservative support for the resolution, the White House paid little attention, and the entire affair was actually covered far more in Panama. Nonetheless Noriega was etched into the minds of Americans as a drug dealer who had to go, paving the way for the execution of a credibility war against him. In the mean time the Department of Justice, Congress, and two Florida grand juries continued to build the case against Noriega.[14]

On February 4, 1988, Noriega was indicted by the Drug Enforcement Agency on charges of conspiracy, racketeering, and cocaine trafficking. Included in the indictment were allegations of millions of dollars in bribes, and millions of pounds of drugs delivered to the United States. While Noriega scoffed at the charges, the White House called for Noriega’s resignation. Privately however, many in Washington worried that the legal strategy employed to remove Noriega could potentially backfire, as Noriega now had no opportunity to safely seek exile. The opportunity for a peaceful resolution to Noriega’s reign became significantly lower following the public indictment.[15]

The indictments were effective in convicting Noriega in the public’s mind, but in little else. The American foreign policy apparatus is very complex, and it was almost immediately clear that these indictments were not the product of organized planning. Many State Department officials did not become aware of the charges until a week before they were announced, with some accusing the Justice Department of making foreign policy. Federal lawyers quipped back, that they were going after a criminal, not making policy.[16]

With the Panamanian government deteriorating, a critical development occurred in early 1988 when President Delvalle attempted, at Washington’s request, to remove Noriega. Delvalle had no system in place to pull off the firing, and so he simply aired a broadcast from a position of safety, in which he declared Noriega’s removal. Noriega responded quickly, airing his own videos in which the command structure re-affirmed their loyalty to Noriega. Delvalle was placed under an unofficial house arrest, and in a meeting of only ten minutes, the National Assembly voted to remove Delvalle, much to the dismay of nearly everyone.[17]

Reagan responded to the ousting with a fresh round of economic sanctions designed to force the Panamanian economy into collapse and subsequently to remove Noriega. Among the sanctions were a removal of Panama’s sugar quota and the stoppage of American business taxes to Panama. In addition, millions of dollars of Panamanian assets were frozen in U.S. banks, along with the federal government’s decision to cease paying taxes on the canal itself. These devastating sanctions have since been estimated to have cost the Panamanian economy over $500 million, and helped bolster support for Noriega’s removal within the Panamanian business class.[18]

While the punitive effects of the sanctions were undoubtedly devastating to Panama, they did not produce the desired effect. The poor and working class ended up feeling the real burden of the sanctions with the PDF and the wealthy coming out relatively ok. As General Frederick Woerner, then head of the United States Southern Command (SOUTHCOM), put it, “We enforced [the sanctions] quite ineffectively because we didn’t want to hurt U.S. business.”[19] It is likely that the regime would have survived if not for the coming invasion thanks to the bountiful and seemingly endless stream of drug revenue coming into the PDF.[20]

In fact, despite the enormous national debt of Panama, the crippling of the Panamanian economy by sanctions, and all the social unrest, Noriega was amazingly still able to increase the size of the military bureaucracy and pay all its members. With the sanctions having failed to dislodge Noriega, discussions of a military intervention picked up in frequency with many in Congress leading the charge for an operation against Noriega, though the Pentagon and the State Department continually debated the scope and the merits of such an operation.[21]

In the early 1980s the specter of communist control of the Caribbean led the conservative United States government to press its influence in Latin America. Though Noriega was initially seen as an ally in the region, over the course of Reagan’s second term, more and more of his illicit drug activities came to light. This was coming at a time when drugs were considered amongst the most important dangers to society. Though Noriega did little to nothing to improve his chances of avoiding conflict, it was clear that by 1986 he was a target. The political climate of the mid 1980s would set the stage for the 1989 invasion of Panama.

[1] Scranton, The Noriega Years: U.S. Panamanian Relations, 1981-1990, 93.[2] Michael Tonry, Thinking About Crime (New York: Oxford University Press, 2004), 45-46.[3] Tonry, Thinking About Crime, 39. [4]The Panama Deception, DVD, directed by Barbara Trent (The American Film Institute, 1992). [5] Doris Provine, Unequal Under Law (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2007), 103. [6] Provine, Unequal Under Law, 104. [7] Provine, Unequal Under Law, 105.[8] Crandall, Gunboat Democracy, 191.[9] Crandall, Gunboat Democracy, 191.[10]Scranton, The Noriega Years: U.S. Panamanian Relations, 1981-1990, 82. [11] Christina Jacqueline Johns and P. Ward Johnson, State Crime, the Media, and the Invasion of Panama (London: Praeger, 1994), 13. [12]Scranton, The Noriega Years: U.S. Panamanian Relations, 1981-1990, 107-108.[13]Scranton, The Noriega Years: U.S. Panamanian Relations, 1981-1990, 119.[14]Scranton, The Noriega Years: U.S. Panamanian Relations, 1981-1990, 110-111.[15]Scranton, The Noriega Years: U.S. Panamanian Relations, 1981-1990, 128-129. [16] Crandall, Gunboat Democracy, 192. [17]Scranton, The Noriega Years: U.S. Panamanian Relations, 1981-1990, 131. [18] Johns and Johnson, State Crime, the Media, and the Invasion of Panama, 11. [19]Army Times, January 1, 1990, quoted in Ivan Musicant, The Banana Wars (New York: MacMillan, 1990), 392. [20] Ropp, “Explaining the Long Term Maintenance of a Military Regime: Panama Before the U.S. Invasion,” 213.[21] Crandall, Gunboat Democracy, 194.